![]()

Climate Debate Gets Its Icon: Mt. Kilimanjaro

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

Published: March 23, 2004

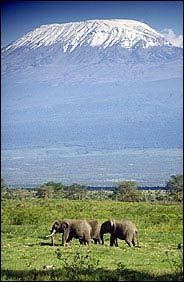

![]() ilimanjaro,

the storied mountain that rises nearly four miles above the shimmering

plains of Tanzania, is beginning to resemble the spotted owl — at least

in the way it has become a two-sided icon in an environmental debate.

ilimanjaro,

the storied mountain that rises nearly four miles above the shimmering

plains of Tanzania, is beginning to resemble the spotted owl — at least

in the way it has become a two-sided icon in an environmental debate.

The

owl first entered the spotlight 15 years ago, in fierce debate over

clear-cutting of ancient Pacific forests. Millions of acres were placed

off-limits to logging when the bird was listed as threatened under the

federal endangered-species law. Soon afterward, effigies of it began

showing up on the grilles of logging trucks.

Kilimanjaro's

majestic glacial cap of 11,000-year-old ice has long captured

imaginations the world over, so it was not surprising that

environmentalists focused their attention on it when scientists

reported in 2001 that glaciers around the world were retreating, partly

as a result of global warming caused by emissions of heat-trapping

"greenhouse" gases from smokestacks and tailpipes.

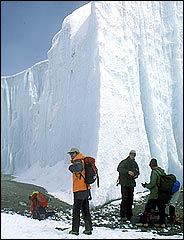

Campaigners

from Greenpeace, the environmental group, scaled the mountain in

November 2002 and held a news conference via satellite with reporters

at climate-treaty talks in Morocco. Last October, Senator John McCain,

the Arizona Republican who is co-author of a bill to curb greenhouse

gases, displayed before-and-after photographs of Kilimanjaro during a

Senate debate. A British scientist proposed hanging white fabric over

the glacier's ragged 10-story-tall edges to block sunlight and stem the

erosion.

But now the pendulum has swung. This

month, the mountain was taken up as a symbol of eco-alarmism by a

cluster of scientists and anti-regulation groups. "Snow Fooling!: Mount

Kilimanjaro's glacier retreat is not related to global warming," read a

newsletter distributed on March 9 by the Greening Earth Society, a

private group financed by industries dealing in fossil fuels, the

dominant source of the heat-trapping gases. "Media and scientists blame

human activity, but a 120-year-old natural climate shift is the cause."

The

group cited a paper in the current International Journal of Climatology

asserting that Kilimanjaro's ice was shrinking because East Africa's

climate is drying, a process that began more than a century ago, long

before humans could have been an influence.

The

authors wrote that the dry weather both limited the snows that help

sustain tropical glaciers and, by reducing cloud cover, allowed more

solar energy to bathe the glacier. In dry, cold conditions, the ice

vaporized without melting first, a process called sublimation. There

was no evidence that rising temperatures had caused the melting, the

researchers said.

So what do these researchers

and the ones who first warned of glacial retreat have to say about the

clashing public portrayals of their work on Africa's highest peak?

Almost

unanimously, they agreed in interviews that the two depictions were

wrong, turning what is still a complicated scientific puzzle into a

simplistic caricature.

The authors of the new

paper said their goal was to challenge what had become orthodoxy about

the mountain — that rising temperatures were eating away at the ice —

and to present an argument for a different mechanism. But their paper

was hardly conclusive, they said. It was mainly a call for more study.

"We

are entirely against the black-and-white picture that says it is either

global warming or not global warming," said Prof. Georg Kaser, the

paper's lead author and a glaciologist at the Institute for Geography

of the University of Innsbruck, in Austria. "As a scientist I'm happy

it's more complex, because otherwise it's boring."

Other

authors of the new study said they were particularly dismayed that the

industry-supported group had portrayed their paper as a definitive

refutation of the idea that melting from warming was involved.

"We

have a mere 2.5 years of actual field measurements from Kilimanjaro

glaciers, unlike many other regions, so our understanding of their

relationship with climate and the volcano is just beginning to

develop," Dr. Douglas R. Hardy, a geologist at the University of

Massachusetts and an author of the paper, wrote by e-mail. "Using these

preliminary findings to refute or even question global warming borders

on the absurd."

In short, Kilimanjaro may be a

photogenic spokesmountain — no matter what the climatic agenda — but it

is far from ideal as a laboratory for detecting human-driven warming.

The debate over it obscures the nearly universal agreement among

glacier and climate experts that glaciers are retreating all over the

world, probably as a result of the greenhouse-gas buildup.

"These

climate skeptics are making generalizations not only to the rest of the

tropics but the rest of the world," Dr. Hardy said. "And, in fact,

global warming may be part of the whole picture on Kilimanjaro, too."

Most

experts in the Kilimanjaro debate accept three things: for more than a

century, its ice has been in a retreat that is almost assuredly

unstoppable and was not caused by humans; so far, there is scant data

on conditions there; and the main scientific question now is how, and

how much, climate shifts driven by heat-trapping emissions are

accelerating that trend.

Dr. Lonnie G.

Thompson, the Ohio State University glaciologist whose work first

focused attention on Kilimanjaro's fading ice, said he saw ample

evidence that melting was eating away at what remained.

His

specialty is extracting cylinders of layered, ancient ice from tropical

glaciers, and when his team drilled into one of the mountain's ice

fields in 2000, water flooded out of the hole. In the resulting cores,

shallow layers contained elongated bubbles — strong evidence of melting

and refreezing — while deeper layers had none.

More

jarring was the violent collapse of a 10-story-tall clifflike face of

one of Kilimanjaro's ice fields in January 2003, witnessed and

photographed by trekkers. The collapse sent a huge cascade of ice and

water gushing across the flanks of the ancient crater.

"This

all suggests that what we are seeing at least in the last 20 years or

so is different," Dr. Thompson said. He believes the mountain may be

close to a threshold at which melting will become the dominant force

eroding the ice. "The balance of evidence says something bigger is

going on in the system," he said.

Dr. Thompson

said that while the new paper selectively described evidence that

drying of African air was the culprit, it did not test that hypothesis.

Perhaps

the long-term drop in humidity is to blame, he went on. "But show me.

Give me something I can see. Otherwise you raise important issues that

need to be studied, and we need data on, but how do you know whether

you're right?"

Several independent glacier

experts who have followed the Kilimanjaro research said the new paper

and Dr. Thompson's earlier assertions about melting were probably both

right to some extent.

But some experts see

signs that something different has been happening in the region in

recent decades. A bit to the north, for example, on the flanks of Mount

Kenya, other scientists have been able to measure shifts in patterns of

ice loss that show solar radiation — the long-term influence on the ice

— is no longer dominating.

Unlike Kilimanjaro,

whose ice is mostly oriented toward the sun, Mount Kenya has ice in

shadow and sunlight. From 1899 to 1962, those ice fields more exposed

to direct solar radiation "wasted drastically" while those in narrow,

shaded grooves changed very little, said Dr. Stefan L. Hastenrath, a

professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, who is a

longstanding expert on African glaciology.

This

implied that changes in cloudiness and sunlight were the dominant force

determining the fate of ice. "But since the 1960's the mountain has

seen more even loss of ice in shaded and sun-exposed ice," he said.

The

editor of the Greening Earth newsletter, Dr. Patrick J. Michaels, a

University of Virginia climatologist, said he did not doubt that humans

were altering climate. He just feels, he says, there is no sign that

humans are pushing matters beyond the natural variability that already

exists — and already must be adapted to.

"I've

written a bunch of papers saying human beings are warming the planetary

surface temperature," he said. "It wouldn't surprise me that you'd see

midlatitude glacier recession. The question is, Why is this alarming?

Aside from the initial shock value of the notion that human beings can

change the climate, why is this such a story?"

But

Dr. Thompson sharply criticized the newsletter's interpretation of the

Kilimanjaro research. "These people get paid to muddy the waters," he

said. "At least we're going out and trying to get the data, which is

hard work. If you're going to sit in your office and send out your

e-mails with no basis, I'm sorry, but that just doesn't carry the day."